Report on Olivier Braunsteffer’s field trip to Peru

In July 2017, the Foundation’s Director travelled to Peru to visit six projects that were at the selection stage, already underway, or completed. As part of its mission, the Foundation organizes regular field visits to gain insight into the complexity of operational contexts, to hear what the various players on the ground have to say, and to engage in dialogue, which is often highly productive. Three intense weeks, the fruits of which were shared on 21 September at the Board of Experts’ annual lunch.

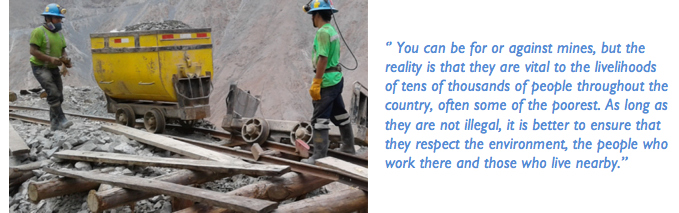

The first visit was to the certified Macdesa gold mine south of Lima. For Mr. Braunsteffer, ‘the results achieved in terms of production and marketing systems as well as environmental protection were undeniable’. He added: ‘One of the challenges ahead for our partner, Alliance for Responsible Mining (ARM) will be to try to include a number of informal mines in their ‘Fairmined’ certification process.’ The complexity of the context should, however, not be underestimated.

Olivier Braunsteffer then joined the Autre Terre teams to see the crops of agroecological avocado, quinoa and tara being produced by the Fruits of the Andes (Frutos del Andes) cooperative. Already well established at Ayacucho on the high plateaux of northern Peru, this cooperative has succeeded in diversifying its production over time and in optimizing its irrigation systems to respond to climate risks. The Foundation did however identify one weak point: the lack of working capital. ‘Fruits of the Andes currently lacks the means to store the crops bought from producers and sell them when prices are more favorable,’ explained Mr. Braunsteffer. ‘How then can sustainability be ensured? This is a vital point, and an area in which the Foundation has the means to take action’.

The third project visited is also at the selection stage. It is located on the Amazonian slopes of the Andes in the Alto Mayo valley, where 70% of the forest has disappeared in favor of monoculture farming (rice or coffee). Conservation International (CI) aims to re-establish forest corridors on the land belonging to the Awajun Indians, as well as more environmentally friendly crops, including the cultivation of medicinal plants in the forest and dozens of local varieties of cassava.

Conversely, CI’s previous project, which the Foundation’s Director visited next, was completed in 2015. ‘The results obtained are astounding! They were already excellent at the end of the project but now they’re remarkable’: coffee plantations in the shade of different species of trees – both fast and slow growing; diversification of production (including vanilla); installation of solar crop driers; use of ecological latrines; development of small livestock farms and lush agroecological market gardens. All this can but strengthen the Foundation’s confidence in its long-term partner and in this type of project.

The next project, run by Nature and Culture International, follows the same theme. One of its farmers raised a serious issue: outbreaks of pests such as the rust fungus (la roya), which seems to be more common under forest cover. A real calamity! Overall, the project is moving forward well. But for Olivier Braunsteffer, further progress needs to be made in implementing agroforestry techniques. ‘We can’t ask producers to plant trees regardless of the risks to their crops and without finding solutions’, concluded the Foundation’s Director, who was also very interested in a CI biodiversity monitoring project on areas farmed under forest cover. ‘This study will help determine whether we are on the right track to find a compromise between agricultural development and biodiversity conservation.’

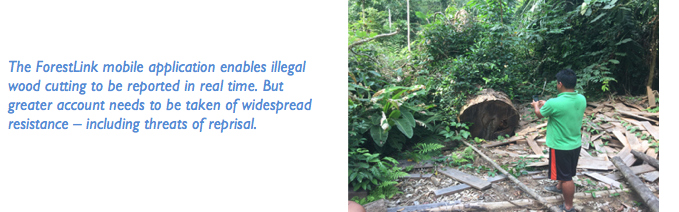

The final visit was to a project run by The Rainforest Foundation UK, which is contributing to the fight against deforestation in the Amazonian region of Peru. Its teams are using a mobile application (see the technical factsheet) with nine Indian communities.

Discussions with the teams on the ground provided a number of avenues for exploration. To optimize the development of this innovative technology, it is indispensable for each context to be taken into account: degree of isolation of the communities, differences in the size of the surface area to be monitored (from 3 000 to 56 000 hectares!), guidance on equipment use and maintenance, risk of violence, women’s involvement in monitoring, etc.

All these issues raised, close to the reality at grassroots level, so that projects can flourish in the best possible conditions – that is the primary objective of this kind of field trip.